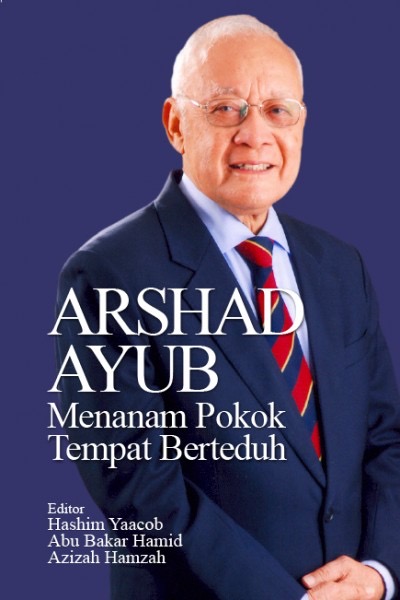

An Introduction To: Arshad Ayub: Menanam Pokok Tempat Berteduh

Editors: Hashim Yaacob, Abu Bakar Hamid and Azizah Hamzah

Penerbit Universiti Malaya, 2018

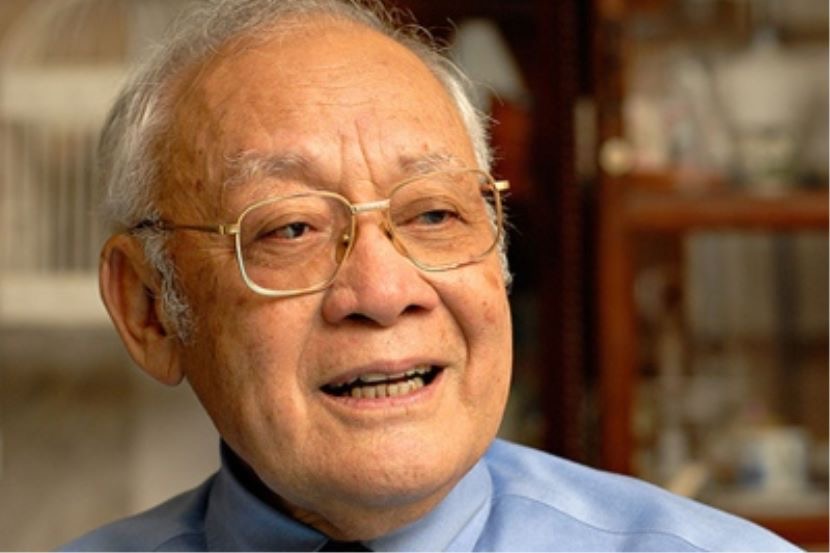

Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Utama Arshad Ayub is a legend with a priceless legacy. The mention of his name is sufficient to bring forth his achievements in almost every field he has been and is in – education, administration, management and NGOs. He is the embodiment of excellence, tenacity and dedication. He is undoubtedly one of the best minds of his generation.

Some would say Arshad Ayub is a godsend to his people. Imagine an Institut Teknologi Mara (ITM) without him during its critical and formative years. Arshad was there not only as its director but a father to the students as well. It wasn’t the best of times. ITM was still an audacious experiment in education. Back then there was a necessity to produce Malay professionals and technopreneurs. Despite the Malays being the majority, they were lacking in professional skills.

Malay students were relatively happy pursuing academic credentials. Nonetheless, the government realised that, without professional skills, they would be left behind in the ever-changing economic landscape. The political masters needed someone with the right vision and discipline to lead the fledgling institute. Arshad has the ferocity of a man in a hurry and the reputation of a feared disciplinarian.

It wasn’t an easy ride for him but failure was not an option. ITM was not there just to provide education or to give an opportunity to Malay students to learn new skills. It was there to challenge them, to jolt them out of their complacency. And challenged they were – moulded into shape as Arshad wanted them to be, without fear and favour. If they survived ITM, they would survive the outside world.

Many factors could have failed ITM. Like any great experiment, ITM could have easily faltered. Arshad was in uncharted territory. ITM was a new frontier, replete with clear and present dangers. Thank God, the government of the day was adamant in ensuring its success. Arshad was given free rein to make it happen. And he took the chance to prove that ITM could succeed. The contrarian in him made the route to success an easier one. A lesser mortal would have failed miserably.

Money wasn’t the only handicap for the new institution. Besides a financial allocation that was never enough, there were insufficient classrooms or lecturers. He had to make do with the resources at hand, which were limited. He had to improvise and innovate while delegating and empowering. His hands-on approach could be exhaustive but he had no choice.

There was another challenge for Arshad beyond academic excellence. The 1960s was an era of ‘linguistic nationalism’. A consciousness for a unifying language was in the air. A new language policy was already in place. A national education system with Bahasa Melayu as the medium of instruction became the totem pole in the academic sphere.

Language purists and crusaders were up in arms against those who were remotely seen as undermining the new language policy. They were demanding that Bahasa Melayu should be the only medium of instruction in tertiary education, in the courts and the administration. ITM initially was not spared.

Arshad stood firm. He had to ensure English as the language of instruction at ITM. He didn’t see any other option. As quoted by Datuk Abu Bakar Hamid in his essay in this collection, Arshad’s answer to his detractors on the language front was classic, “I am here to save the Malay race, not the Malay language.”

Some would argue that was a simplistic reasoning by Arshad to avoid the issue. But he was adamant. English is an international language, not just a language of commerce and finance. As evident now, English is the language of the wired world. The official language of the Internet. Arshad took full responsibility for sticking to his language policy, much to the angst of some of his critics. He got away with murder, so to speak. And he has been vindicated.

Arshad encouraged not just fluency in English but other languages too. In fact, he believed in the importance of being trilingual. Mandarin, Tamil, Japanese, German, French and Russian were introduced at ITM.

What was important, however, was the variety of courses that could be undertaken by students. During his time, 68 “practical and professional” courses were offered, from accountancy to banking to mass communication. It wasn’t easy to get lecturers for the courses.

The talent pool was overstretched. He also wanted people with working experience to teach the students. It wasn’t about theory but practice. The graduates wouldn’t be able to survive just by learning theories in class. They needed practical training as well. Those courses were geared for industry requirements.

There was another sure-fire recipe for failure if Arshad was not vigilant – the students themselves. Many came from rural areas, uprooted from their complacent surroundings and thrown into an institution that demanded more than just hard work. It was about changing mindsets too. Arshad knew these students had potential. But to change the culture was another issue. They needed confidence, self-esteem and the winning spirit. And, more importantly, the ability to communicate and articulate well.

The kampung mindset had to be addressed. The cultural baggage was a burden.

Arshad tinkered even with the dietary habits of his students. He introduced bread for breakfast, a dramatic change from rice-based diets. His infamous experiment to give students bread instead was legendary. The so-called ‘bread saga’ of ITM was, in fact, a euphemism for ‘change’. It was symbolically a paradigm shift for the students. Perhaps he proved a point – change your eating habits, it will change your lifestyle.

Arshad has always believed in building values that are essential to success in the ever-changing dynamics of society. He whipped the students into shape with discipline, and a lot of cajoling too. He expected the best from them. While the readiness to compete is critical, discipline is the key. He did it his way. Nonetheless, these students were grateful to him for instilling in them discipline and hard work.

This is evident in some of the essays in this collection written by those who were there during the frightening years of living under Arshad’s leadership. He taught them the meaning of self-respect, credibility, dignity and accountability. And the readiness to compete. They were no more juara kampung but the pride of the nation.

Graduates of ‘Arshad Ayub’s System’ – more than 700,000 of them at the last count – are reshaping the nation, redefining excellence and helping to restructure society. With ITM’s success, the Malays could no longer claim to be left out of the professional sphere.

The New Economic Policy (NEP), however controversial it was, might have not achieved the desired results but, at least, it addressed the issue of equity and imbalance among the races. There are many Malay boys and girls from ITM who are now corporate leaders and successful businessmen. Others are movers and shakers in their fields.

Arshad spent 10 years at the helm of ITM. Today ITM is known as Universiti Institut Teknologi Mara (UiTM). It is currently the biggest university in terms of students and number of campuses in the country. As reported by R Zeeneeshrie in a piece in the New Straits Times in conjunction with UiTM’s 71st convocation ceremony, besides its main campus in Shah Alam, UiTM has three satellite campuses, 15 state branch campuses, nine city campuses and 19 community colleges. Currently, it has 120,000 students with 15,000 staff.

Undoubtedly, Arshad has a share in the success of the university today. He was the architect who shaped ITM into what it is now. His vision has had a long-lasting impact on thousands of its students.

Arshad had every reason for wanting young Malays to succeed in education. He is himself a case study of a rag-to-riches story. He came from a destitute family. He knew what education could do for people. Education changed him. He could have been, like his father, a rubber tapper, trishaw-puller or labourer. But he was given a second chance. He seized it and the rest is history.

Arshad is the eldest in the family. His father died when he was young. He had to carry the burden of helping to feed the family. He was a sickly kid too. Yet he persevered. He knew that only education could unshackle him from the yoke of poverty.

The book, A Second Chance: Life and Mission of Arshad Ayub, written by Rokiah Talib is an inspiring story of a young man who almost didn’t make it. I have always recommended the book to be read by all. It is about the making of a real champion – a giant among his peers, an icon among his students and an exemplary citizen of this proud nation. Like Arshad said, this book is not just about him, it should be “our book” – the book that everyone can relate to and learn from.

As related in the book, Arshad did relatively well in his studies, yet he was denied entry into the University of Malaya in Singapore, the cradle of academic excellence in the country and region. He went to the College of Agriculture in Serdang instead. But he had a dream. The sky was the limit. He wasn’t a young man when he went to the University College of Wales at Aberystwyth to study economics and statistics in 1954 – a major setback for many others, but not for Arshad.

ITM is just one of his many stellar achievements in life. He is undoubtedly one of the country’s best minds in education, which is still an arena close to his heart. That he was honoured as a recipient of the coveted Merdeka Award in Education and Community speaks volumes of his contributions.

The editor of A Second Chance, Hamidah Karim, wrote that the book is about “how Arshad built three levels of commitment around his work. Firstly, his own vision of ITM vis-à-vis the supra-objectives of the NEP; secondly, his strategy for marketing ITM graduates and making them more acceptable to the private sector and, finally, ensuring that through their participation in the private sector, they would further improve the position and future of the Bumiputera community.”

I couldn’t agree more with that observation.

I am a great admirer of Arshad Ayub. He was a kampung boy who made it in life. He was born 27 kilometres from where I was born and grew up. Both of us are Scorpions – born in the month of November; I was born on the ninth, he on the fifteenth, though 25 years apart.

We are proud Muarians. At one point I went to the same school, Muar High School, of which he was a student many decades earlier. Like his father, mine was a rubber tapper. Like him, I endured poverty. But living in a remote village of Sungai Balang Besar in the 1950s and ‘60s was different from growing up in Parut Kurma Laut in the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s. Things were tougher for him.

I have known Arshad for many years. I was fortunate to have crossed paths with him in various capacities. We were on the same board of a public listed company some years ago. I have seen him in action – tough, forthright, firm, but a fair and just board member. As chairman of the audit committee of the company, he would literally scrutinise every minute detail with a magnifying glass. I joked with the board members that forensic auditing had been invented by him.

Arshad is a true gentleman. He is always the father figure and the voice of reason and conscience on the board. While any CEO may have sleepless nights at the prospect of facing him in board meetings, he is always there to help, guide and mentor. He takes a strong position in good governance and integrity. Companies are blessed to have him on their boards.

I am honoured to be part of this book project. I didn’t hesitate for a moment when Datuk Professor Emeritus Dr Hashim Yaakob spoke to me about writing the Introduction to this book. I must also commend Professor Dr Azizah Hamzah of University Malaya’s Media Studies for being kind enough to provide me with an overview of this book.

There are eleven essays on Arshad Ayub written by his friends, colleagues and former students. These essays come from the heart – you can sense the sincerity and frankness in each piece. Words and phrases are merely tools to render their feelings and emotions for the man.

They have great narratives to tell about Arshad – not really surprising as he connects with people in more ways than one. The title of this book is Arshad Ayub: Menanam Pokok Tempat Berteduh. I would like to look at Arshad as a catalyst for the advancement of our society, one whose vision and mission helped to shape it. Arshad is that and more, for he is not just an icon but an institution.

This book is edited by three outstanding individuals: Datuk Dr Hashim Yaakob, Datuk Abu Bakar Hamid and Dr Azizah Hamzah.

I am delighted to read the essays that are written in many forms – some in an academic format, others with a more laidback style. The collection of essays provides narratives in the making of this exceptional personality.

Datuk Abu Bakar Hamid’s illuminating piece, ‘Berani Menguak Takdir: Cabaran Hidup Tan Sri Arshad Ayub (Wading Through Destiny: The Challenging Life of Tan Sri Arshad Ayub)’, sets the tone of the discourse. Not at all condescending, it opens up Arshad, warts and all, to discerning readers. Abu Bakar’s scholarly approach has the right amount of information to place Arshad in the context of history of his negara bangsa (nation state). We have a lot to learn from this essay.

The one written by Dato’ Kapten Emeritus Prof Dr Hashim Yaacob (Rtd), a former student of ITM who later became Vice-Chancellor of the University of Malaya, is simply outstanding. His narration on Arshad is strewn with poems specially written for the purpose. It is a fresh approach at ‘appropriating’ the discourse on ‘Arshadism’ – the man he hugely respects and admires. Little wonder that he titled his essay ‘Tan Sri Arshad Ayub Merata Tanah Tempat Bersila’ (Tan Sri Arshad Ayub Levelled the Playing Field).

Hashim starts with these lines:

Orang membelah atom

Arshad Ayub membelah matahari

(Others dissect an atom

Arshad Ayub dissects the sun).

An accomplished poet, Hashim uses matahari (the sun) to symbolise Arshad’s gargantuan task at ITM back then.

Tan Sri Dzulkifli Abdul Razak uses the term samseng (gangster) to reflect students’ reactions to Arshad’s uncompromising position on discipline. He hits the nail on the head by concluding that “ITM itu Arshad, Arshad Itu ITM (ITM is Arshad, Arshad is ITM).” No one will contest that statement even today.

Another product of ITM’s system is Datuk Paduka Ibrahim Ali, a student leader during the tumultuous 1970s. A firebrand himself, his unpredictability is legendary; he is a politician of many facets, yet, he has nothing but praises for Arshad. The title of the piece succinctly explains his admiration for the man: ‘Arshad Ayub – The Saviour’.

Emeritus Professor Dato’ Dr Hassan Said writes about Arshad’s contributions in the development of ITM. Dr Hassan was the Vice Chancellor of UiTM. Understandably he reflects on Arshad’s contribution to the institution he once led. UiTM is blessed for Arshad has built a strong foundation during its fledgling years. Arshad is undoubtedly an integral part of the glorious history of UiTM.

Another successful graduate of ITM is Datuk Zaini Hassan, a senior editor at the Utusan Melayu group of newspapers. He is currently President of the UiTM Alumni Association. Zaini’s corat-coret (titbits) on Arshad is refreshing to read.

Also a grateful graduate of ITM, Professor Emeritus Ezrin Arbi had migrated from Indonesia to Malaysia. His essay, ‘Arshad Pengubah Jalan Hidup Saya (Arshad Changed My Path in Life)’, is full of surprises. Taking the perspective of a first-hand account, Ezrin’s debt of gratitude is understandable. Ahmad Murad Merican is likewise a proud product of ITM.

A media scholar and critic in his own right, Ahmad writes about Arshad’s contributions in nurturing the rise of a new Malay/Bumiputera intellectual. Ahmad acknowledges the role Arshad played in promoting the study of mass communication at ITM from which he graduated, like thousands of others over the years. He believes that for graduates of that discipline, many of whom are now holding important positions in the media world, Arshad is the ‘Father of Malay Intellectuals’.

Professor Kurunathan Ratnavelu’s essay, ‘Arshad Ayub – As I Was Passing!’, is rich in anecdotes of his personal encounters with the man. He was once Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Development) of the University of Malaya when Arshad was chairman. He saw Arshad up close and personal and admired the latter’s uncompromising stand on integrity. He was enriched by the experience of working under Arshad’s leadership. But he also saw the human side of Arshad, his wit and humour.

“Attitude” or sikap is probably one of the most ferociously debated concepts for any race in transforming itself for the better. The Malays are no exception. There have been a lot of soul-searching for the Malay race since the early 20th Century. The debate on old values and new, on the role of religion and the need for a mental revolution have been part of Malay consciousness since then. So the essay by Md Azlanshah Md Syed on how Arshad has contributed to the changing mindset of young Malays, particularly those who went through his “system” at ITM is extremely relevant.

There is a piece by Professor Dr Azizah Hamzah, which looks at a broader perspective of knowledge associated with Arshad Ayub. She believes Arshad is an architect of knowledge. She argues that what we need is not just ilmuan (people with knowledge) but, more essentially, those using knowledge for the betterment of mankind. We require intellectual leaders too.

In an ever-changing world, we need STEM (an acronym for the academic disciplines of the sciences, technology, engineering and mathematics) to bring the country to the next level. But that alone is not enough. Quoting the legendary founder of Apple, Steve Jobs, Azizah points out that Apple’s DNA is technology “married with liberal arts and married with the humanities that yields us the results that make our hearts sing.” She believes Arshad is a fanatical believer in that concept.

There is an interesting essay by Dato’ Dr Koh Boon Cheng in this collection. He was first introduced to Arshad Ayub in 1967 and, over the last five decades, they became more than colleagues. Dr Koh has seen Arshad Ayub first-hand as an administrator and later the head of the fledgling institute, the then ITM. He was with Arshad Ayub when the latter visited the new ITM campus under construction at Shah Alam in 1969.

Dr Koh was entrusted with the health of the students, most of whom came from villages all over the country. On Arshad Ayub’s instruction, he set up a clinic for the students at the Jalan Othman, Petaling Jaya campus.

Dr Koh has a sub-heading in his essay, “To Raise Me Up to More Than I Can Be”. It is the title of a song originally composed by the Irish-Norwegian duo, Secret Garden, and later made famous by, among others, legendary Josh Groban and the teen sensation, Westlife. The song has these lyrics:

“You raise me up, so I can stand on mountains;

You raise me up to walk on stormy seas;

I am strong when I am on your shoulders;

You raise me up to more than I can be.”

The song captures the essence of a fatherly figure providing support and guidance to others; in the case of ITM during its formative years, poor students from the Malay heartlands. Arshad Ayub was there to raise them up to more than they can be. As pointed out by Dr Koh, Arshad Ayub was a disciplinarian but, like a father, he was there to ensure them the route to their success.

Dr Koh named names – those who have succeeded beyond their dreams. A few of them even contributed to this collection of essays. They will be etched in the hall of ITM (UiTM) fame. The university is proud of them and they have every reason to be proud of their years at the institution.

Last but not least, there is a write-up by Tuan Nurizan Raja Yunus based on an interview with Dato’ Dr Hassan Mad, the Secretary-General of the Malay Consultative Council (Majlis Perundingan Melayu). It is about Hassan Mad’s impressions and observations of Arshad Ayub as a thinker, teacher and administrator. He has nothing but praises for the iconic fellow-Muarian.

There is one observation that helps define the man – how Arshad Ayub expects “extra” from others. He sets a good example for others to follow, leading as they say, by example. Hassan Mad also reminds us that Arshad Ayub made the best of situations. Even when placed in a cubicle not befitting of his status at one point of his career, he did not complain: “It’s ok, it is a new experience, not many people have this experience.” He soldiered on, giving his best and not complaining.

We need to look at Arshad’s leadership style to complete our understanding of the man. He should be studied by students of management as a case study. Perhaps by reading what have been written about him (including this collection of essays), the real Arshad Ayub will surface. I sincerely hope his management principles will be taught in management schools here and abroad.

Arshad Ayub has done so much for UiTM. Therefore it is a fitting tribute to him that the university attached his name to a business school – Arshad Ayub Graduate Business School (AAGBS). It has become the most outstanding graduate school at UiTM. It offers Master of Business Administration (MBA) as well as Master of Islamic Banking and Finance (MIBF), Doctor of Business Administration (DBA) and Doctor of Philosophy by Mixed Mode (PhD).

According to its prospectus, the school “provides an understanding of strategic business models, contemporary issues and appreciation of responsible and sustainable leadership values that are very much in demand in today’s market.”

I commend the current leadership at UiTM for the initiative. Arshad Ayub is indeed a role model in business acumen and leadership. Thus the school that carries his name has to live up to it by producing graduates who are not only familiar with current business trends, able to embrace good practices and governance, understand the clear and present dangers of today’s challenging business atmosphere but also remain rooted to the core values and ethics of our culture, tradition and religion.

Fittingly, this collection of essays is a tribute to the man. His career spanned at least seven decades, yet he is not showing any sign of slowing down, even at 90.

I believe this indefatigable crusader of excellence will continue to make his mark many more years to come.

Insya Allah (God Willing).

Teruskan melakar peradaban, Tan Sri Arshad Ayub! Bangsamu terhutang budi kerana pokok yang kau tanam untuk menjadi tempat mereka berteduh selama ini!

- TAN SRI JOHAN JAAFFAR is a journalist, editor and writer. His love for the arts never faltered, despite his years in the media and corporate world. He has just published a book, ‘Jejak Seni Johan Jaaffar: Dari Pentas Bangsawan ke Media Prima Berhad’, about his 50-year incredible journey as an actor, playwright, director and chairman of the country’s largest media company that produces thousands of hours of creative content. He considers himself an admirer and friend of Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Utama Arshad Ayub.